Canadian Masters and their Works

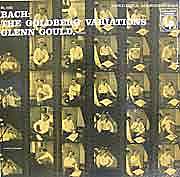

Glenn Gould – Goldberg Variations / Bach – 1955

“A performance of originality, intelligence and fire.” Tim Page

Glenn Gould –A conversation on the Goldberg Variations

Glenn Gould –A conversation on the Goldberg Variations

Only a handful of recordings of the Bach’s opus BWV 988 existed before Gould’s time, including the very first recording and the one that cornered the market: Wanda Landowska’s complete Goldberg Variations on harpsichord (1931). She also gave the first complete public performance in the 20th century of the work during 1933. Nearly twenty-five years later, in 1955 Glenn Gould would change the recorded history of that piece and leap into fame. He began and also concluded his recording career in 1981 with the Goldberg Variations. On August 22, 1982, a short time before his death, Gould met Tim Page (who edited the Glenn Gould Reader) to discuss his performances of the Goldberg Variations. The following are excerpts of this conversation. Gould shares his unique vision (which was controversial in some circles) of the central work of his recording career. Here he explains the quintessential idea of rhythmic continuity.

Jean-Pierre Sévigny

“I have a theory vis à vis my own work anyway, or something less grand than a theory really; it’s more a speculative premise (…) I think that the great majority of the music that moves me very deeply is music that I want to hear played or want to play myself, as the case may be, in a very illuminating, very deliberate tempo (…) A firm beat, a sense of rhythmic continuity has always been terribly important to me.”

“All the music that really interests me, not just some of it, all of it, is contrapuntal music, whether it’s Wagner’s counterpoint, or Schoenberg’s, or Bach’s (…) The music that really interests me is inevitably music with an explosion of simultaneous ideas, which counterpoint you know when it’s at its best is; and it’s music where one I think implicitly acknowledges the essential equality of those ideas, and I think it follows from that that with really complex contrapuntal textures one does need a certain deliberation, a certain deliberateness.”

“I’ve come to feel over the years that a musical work, however long it may be, ought to have basically, I was going to say one tempo, but that’s the wrong word, one pulse rate, one constant rhythmic reference point (…) You can take a basic pulse and divide it or multiply it, not necessarily on a scale of 2, 4, 8, 16, 32 but often with far less obvious divisions, I think, and make the result of those divisions and multiplications act as a subsidiary pulse for a particular movement or section of a movement. And I think this doesn’t in any way preclude rubati (“freedom of tempo, shortening the duration of some beats and adding to others”). If you have an accelerando (“faster passage”) for example, you simply use the accelerando as a transition between two aspects of the same basic pulse.”

“So in the case of the Goldberg, there is in fact one pulse, with a few very minor modifications (…), that runs all the way throughout.”

Used with the kind permission of Tim Page.

Links

http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=U1ARTU0001410

http://www.glenngould.com/

http://www.collectionscanada.ca/glenngould/index-e.html

http://www.glenngould.ca/index.nn.html